As a historian who works on the U.S. Navy in the early republican era, I have found that many, if not most, of my sources have been published in some form. Many have been published both in print and online. So when I go to an archive to look at manuscripts, there’s a strong chance that the documents I look at have already been published. Thus, it might seem like photographing manuscripts, particularly in big federal archives like the Library of Congress or the National Archives, is a waste of my time.

However, there are several reasons I’ve found it worthwhile to photograph manuscripts, despite the near certainty that I’m redoing work someone else has already done. First, many does not equal all. Documents not deemed to fit into the argument of the collection are left out of print collections, and most of the time digital archives merely duplicate the printed collections, rather than sweeping up documents left behind in the original selection. This practice makes sense on a certain level—for instance, it’s not unreasonable to exclude from a collection of Madison papers documents that don’t mention him at all. But a research question about consular practices during Madison’s tenure as secretary of state might benefit from more obscure documents that don’t relate directly to Madison himself. Therefore, I find it worthwhile to go hunting for those unpublished documents, even if it means wading through a large number of already-published ones.

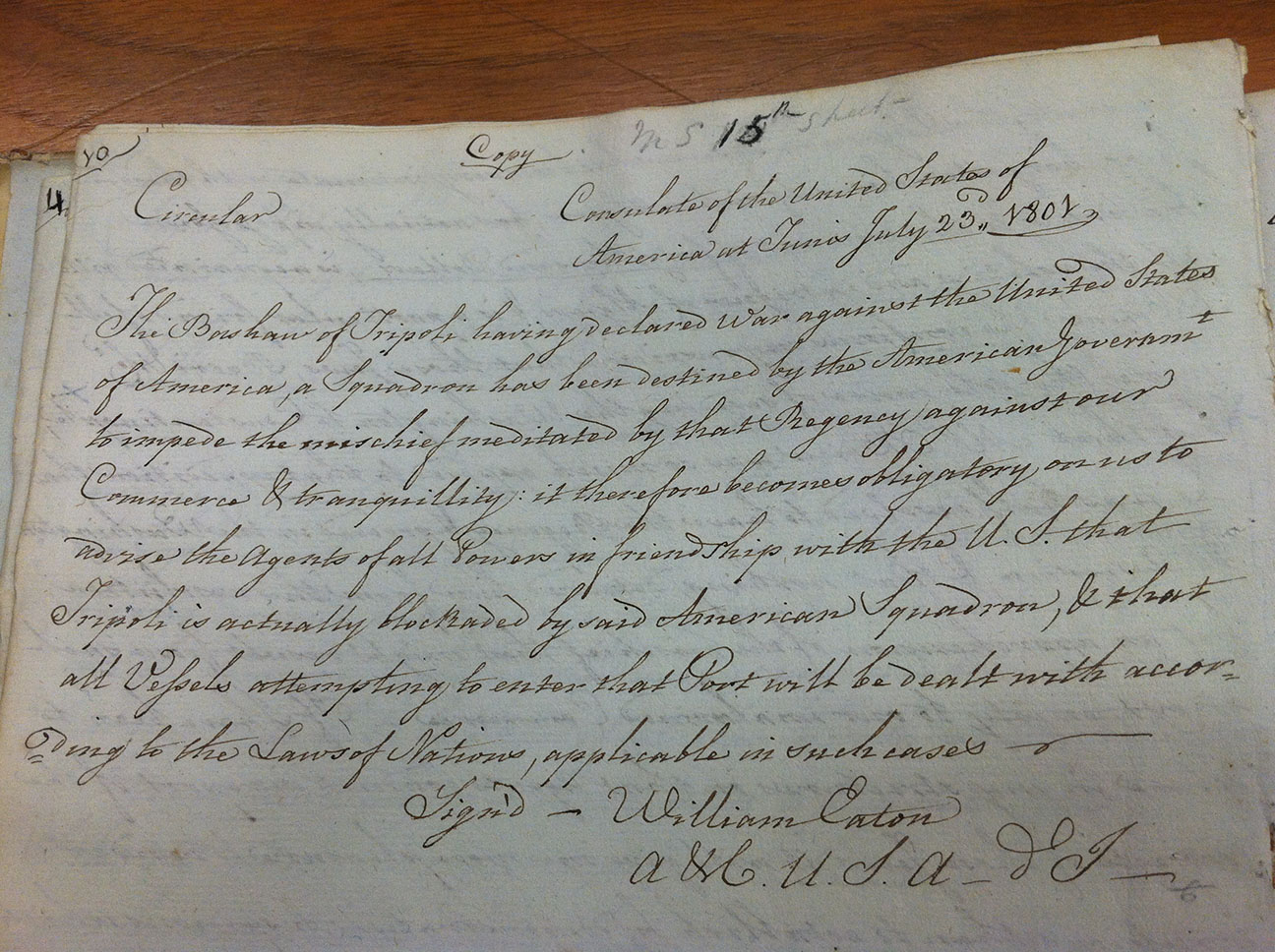

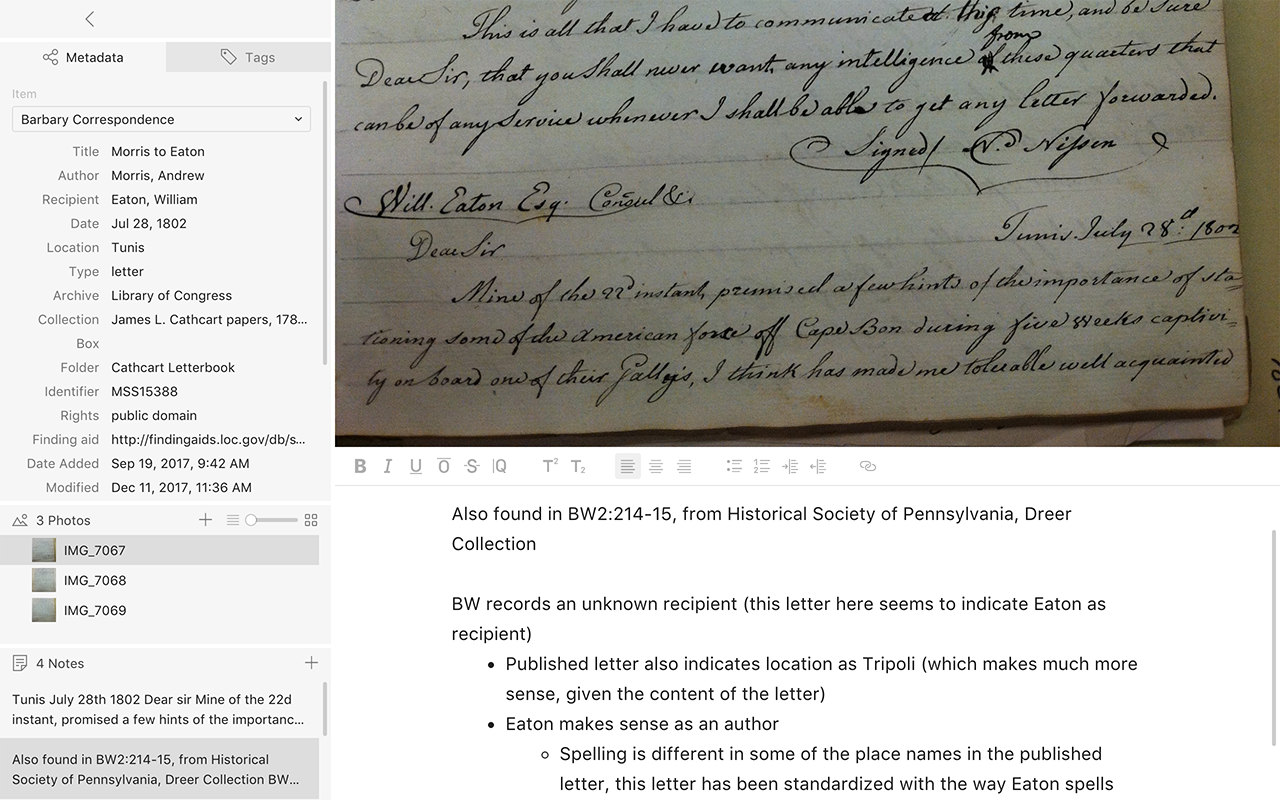

Second, I’ve found that the manuscripts I see in the archives do not always exactly match the published ones. Because of the practice of writing out multiple copies of correspondence in the 19th century (and before), the source for a published letter might not be an exact duplicate of one in a different archive. For instance, a letter written by Captain Andrew Morris in July 1802 is published in the Navy Department’s document collection. In the published collection, the letter is headed “To whom addressed not indicated, presumably James Leander Cathcart.” The letter is transcribed from a copy in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. However, the same letter appears in the manuscript collection I photographed at the Library of Congress, this time addressed to William Eaton. Given the content of the letter, Eaton makes much more sense as a recipient, and the letter appears in a section of a letterbook entirely devoted to letters sent or received by Eaton. There are some other irregularities, including a discrepancy in where the letter came from (the HSP letter says Tripoli, the LC says Tunis). The errors and omissions signal the great speed and frequency with which the diplomats of the Mediterranean copied and re-copied their letters. Having both letters allows me as a historian to determine which facts fit into the larger narrative, an opportunity I wouldn’t have had if I had just skipped this letter because it was already published.

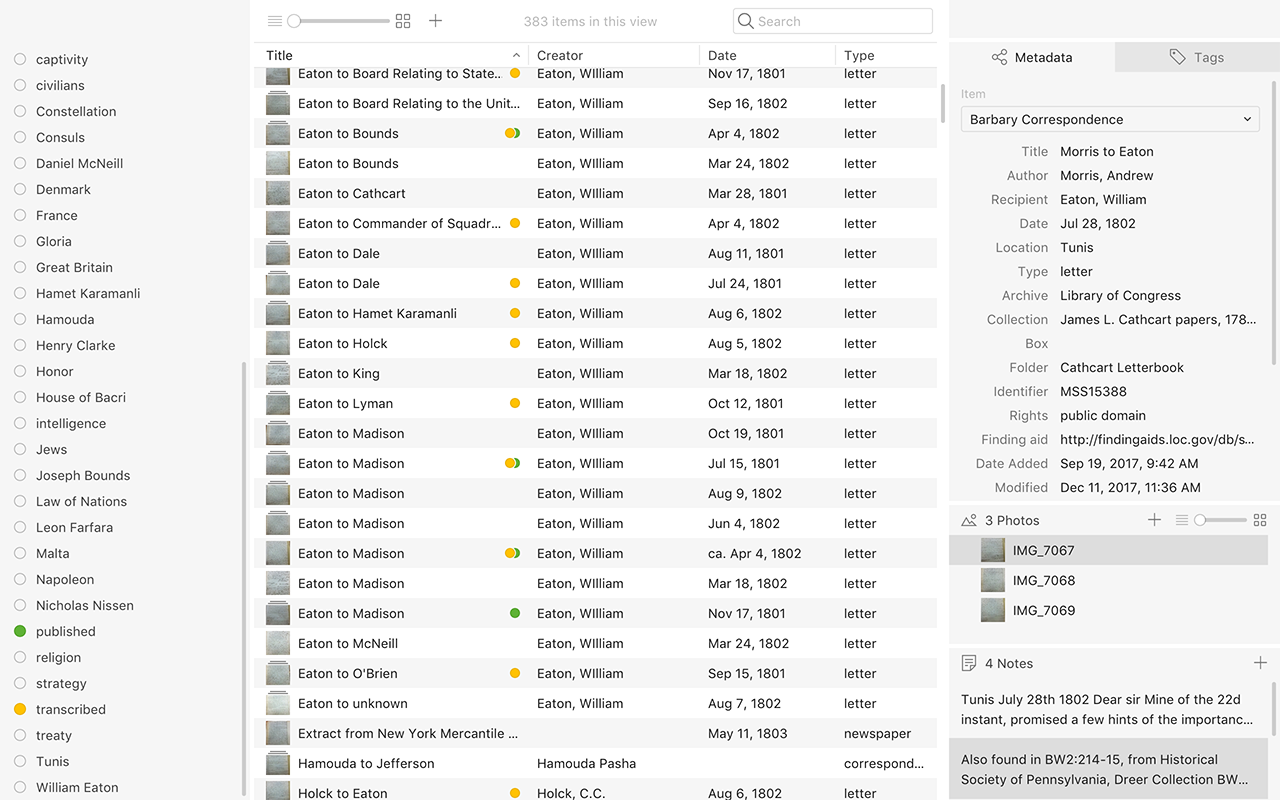

Tropy allows me to be systematic as I record where documents came from and where else they might be held. All of that information can be held in Tropy, making it easier to access it if I need it. I use a combination of metadata, tags, and notes to keep track of all these different pieces of information.

Metadata

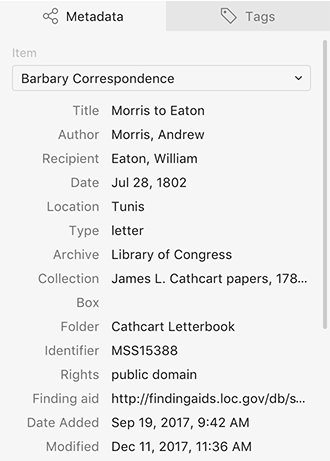

Tropy’s metadata templates are the first place to start for organization, no matter what your sources are. Most of my sources are letters, so I started with Tropy’s standard “Tropy Correspondence” template. As I worked, I discovered that I could make a few minor changes to that template that would allow me to store even more information. For this template, I simply added a field to the template allowing me to include a link to an online finding aid. That way, I could get straight back to the catalog’s records about the larger collection, rather than having to search through the catalog to find these sources again. Thus, the “Tropy Correspondence” template became my own customized template, “Barbary Correspondence.”

Tags

My metadata templates give me as much information as I need to find the sources I’ve photographed. But to track other instances of my sources, I need a more complex system. I could add a field to my template to indicate other sources of publication, but I wanted to be able to see at a glance which of my sources have been published elsewhere. Tropy’s colored tags allow me to instantly see important categories across my whole project. However, overuse of colored tags just creates a muddle. I have dozens of content-related tags (people, places, thematic elements), but I’ve chosen to use my colored tags to mark information about the documents themselves, not their content. Therefore, I have only two colored tags at the moment: transcribed and published.

Notes

The final piece that allows me to track publication of my sources is the notes field. My goal is to transcribe everything I have (remember, I don’t actually have that many photos), so right now I use notes mostly for transcription. But for every document that I find published elsewhere, I create a note about its location and any discrepancies with the source in my photo. I could put this information in the metadata template, but it’s long and idiosyncratic enough that I found it easier to do in notes.

Conclusion

Tracking duplicates is one way I can streamline the reading of published sources: as I find something published in a collection, I don’t have to wonder, “Have I seen that before in my photos?” I can go check using the metadata I’ve filled out about my photos. And if it turns out that I have it in my photos already, I can make a note and then continue on my way, rather than mindlessly reading the same document over and over again.